Chef Ignacio Echapresto, and his brother Carlos, sommelier from Venta Moncavillo Restaurant.

The town of Daroca would not be very well known even in La Rioja were it not for the fact that its population doubles and often triples twice daily. The pilgrimage is not on the Camino de Santiago. The experience these devotees are seeking is much more hedonistic and self-indulgent. It occurs at mealtimes.

Daroca is a very small village off the A-12, about 20 minutes south of the capital, Logroño. There are exactly 24 people who live there. It is an unlikely spot for a Michelin Star restaurant, but defying the odds is Venta Moncavillo. Here, chef Ignacio Echapresto and his sommelier brother, Carlos receive the world in Daroca.

So rooted in their village, and proud of their Riojan rural heritage and cuisine, Chef Ignacio decided to turn his back on the capital city, and chose to open his restaurant where it suited him. He describes it as a “lifestyle choice”.

Carlos and his mother

The restaurant is a family business with their mother working on site daily keeping the kitchen clean and running. It may sound like a menial job, but there was no doubt in my mind that she is the matriarch of the Echapresto family.

The hands of Chef Ignacio and his sous-chef Pablo from Argentina, skillfully prepare the food for the restaurant, with a seating of 60.

Chef Ignacio Echapresto

Chef Ignacio explained that his inspiration for his seasonal menus comes from the foods that he grew up with, but the style is not at all rustic. It is as refined as any urban Michelin Star restaurant. The food is as fresh as it gets. The produce comes directly from a large Huerta located behind the restaurant. Local farmers and hunters bring their catch to him.

I was allowed unusual access to the inner sanctum of this restaurant not as a client, but as a participant. It was agreed that I would spend two days working at the restaurant in order to see the chef, the sommelier, and the staff in action. I was assigned to an Italian waitress, Valentina, a veteran in fine dining, who spoke Spanish, Italian and English fluently and to my great relief I could communicate with her in two of those languages.

Just before opening, Chef Ignacio surveyed the dining hall (for large groups), straightened a few napkins, much as a director would do before the opening of a show. I quickly realized that every night in this restaurant is like opening night and Ignacio expects perfection from everyone. He told me, “Don’t do anything unless Valentina or myself tell you to do it.” My reply, “Yes chef.” It was clear that my presence caused a little bit of stress for staff— I was an extra, but one with not much experience. If I were to mess up, it would negatively impact the whole production. Valentina reviewed the rules: “Serve from the right, start at the end of the table and work your way to the door. I’ll take the other side. Do you know how to serve bread rolls with just the fork and the spoon?” “No, but if you show me, I could probably do it.” “Never mind, I’ll do it, you serve the water.”

The first to arrive was a group of 12 foreigners all driving rather expensive fast cars. They were escorted to the wine cellar for aperitifs and appetizers. Carlos proudly displayed his 600 bottles for selection from the best vineyards, from the best years from wine areas worldwide.

Up in the kitchen, I expected more noise, more confusion as twelve people needed to be served at once. There was no rushing, no banging of pots, not even any talking. It was orchestration at its finest. Ignacio and Pablo worked in tandem---they remained calm but focused, attentive. Each plate was replicated with exactness, with the plate’s design in the top right hand corner, and the wait staff presenting each masterpiece to the customer in exactly the same way.

Course after course was served; wine after wine and I became cognizant of all the decisions that had to have been made, all the rehearsals that preceded the delivery of the plate to the customer. In this restaurant it began almost 3 months before this night when Master chef Ignacio reviewed the seasonal foods that would be available to him for the new coming season. He re-created a new seasonal symphony, harmonizing tastes, and designing a presentation that could not but visually delight.

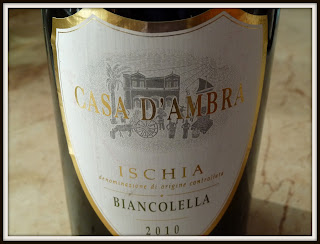

On my second day, before the guests arrived Carlos asked me to arrive an hour early for a wine tasting. He treated me to 14 different Spanish wines described at the end of this entry. Carlos enjoyed sharing his knowledge of the Riojan wines until his brother the Master Chef told us it was time to get ready for the next round of guests. It was showtime again, and the brothers Echapresto would not disappoint.

My only regret (other than not wearing comfortable shoes) is that I did not get to try the food. The staff does get to eat, but they eat the rustic cuisine that Ignacio and Carlos grew up with: the staff eats what Mamma cooks.

I wish there were some way that I could meaningfully thank the Echapresto family and their staff, for giving me a front row seat where taste and smell are the artists palette, the canvas a simple white dish and service is a carefully orchestrated ballet. Perhaps you can help me in this regard. If you happen to find yourself in La Rioja, will you go and have a meal at Venta Moncavillo? Please tell them I sent you.

Venta Moncalvillo Restaurante

Ctra. Medrano 6

Daroca de Rioja

26373 La Rioja

to reserve: +34 941 44 48 32

www.ventamoncalvillo.com

GPS: N 42° 22' 20" W 2° 34' 50"

The first 3 wines were given to him to taste in unmarked bottles from "a" winery. The most interesting of the wines we tasted that day were from Finca Antigua, their wine called Clavis, 2004 from their vineyard Pico Garbanzo in La Mancha: deep purple with ruby rim, ripe red berries, herbaceous, sweet oak, clarified with egg whites. There were hints of green pepper. Carlos said he detected an aroma of burlap, which I guess is much like the smell of hay. There was no indication on this bottle what the varietals might be, but their Crianza 2007 listed Tempranillo, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah so I’m guessing it was some variety of these. Another highlight was a wine from Bodegas Ramòn Bilbao and their Edición Limitada 2009. This wine is 100% Tempranillo. The wine was a deep red. The first aroma to arise was a smoky, charred toastiness followed by ripe red berries, and prune. This wine had bright acidity and the aromas and flavors presented themselves in complete harmony. I have one more favorite: LZ from Compañia de Vinos de Telmo Rodriguez. This wine set itself apart by adopting a modern, intriguing label, but more importantly it offers good value for money. This is a young (joven) wine and sells in Spain for about 6 euros. It is made of a blend of Tempranillo, Garnacha and Graciano—the 3 classic varietals of La Rioja. I loved the earthiness of this wine and it is truly reminiscent of French wines. (I know that people say that La Rioja is the Bordeaux of Spain, but the earthiness of some of the wines that I tasted bring me back to some Burgundy Pinot’s): damp earth, mushroomy. I know this was not the most expensive wine that I tasted that day, but it was my favorite. Other wines that I had the pleasure of tasting were Distercio, by Florentino Martinez aged in Riojan Oak, a Roda Riserva 2006, once again with a comfy earthiness wafting from the glass.

The first 3 wines were given to him to taste in unmarked bottles from "a" winery. The most interesting of the wines we tasted that day were from Finca Antigua, their wine called Clavis, 2004 from their vineyard Pico Garbanzo in La Mancha: deep purple with ruby rim, ripe red berries, herbaceous, sweet oak, clarified with egg whites. There were hints of green pepper. Carlos said he detected an aroma of burlap, which I guess is much like the smell of hay. There was no indication on this bottle what the varietals might be, but their Crianza 2007 listed Tempranillo, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah so I’m guessing it was some variety of these. Another highlight was a wine from Bodegas Ramòn Bilbao and their Edición Limitada 2009. This wine is 100% Tempranillo. The wine was a deep red. The first aroma to arise was a smoky, charred toastiness followed by ripe red berries, and prune. This wine had bright acidity and the aromas and flavors presented themselves in complete harmony. I have one more favorite: LZ from Compañia de Vinos de Telmo Rodriguez. This wine set itself apart by adopting a modern, intriguing label, but more importantly it offers good value for money. This is a young (joven) wine and sells in Spain for about 6 euros. It is made of a blend of Tempranillo, Garnacha and Graciano—the 3 classic varietals of La Rioja. I loved the earthiness of this wine and it is truly reminiscent of French wines. (I know that people say that La Rioja is the Bordeaux of Spain, but the earthiness of some of the wines that I tasted bring me back to some Burgundy Pinot’s): damp earth, mushroomy. I know this was not the most expensive wine that I tasted that day, but it was my favorite. Other wines that I had the pleasure of tasting were Distercio, by Florentino Martinez aged in Riojan Oak, a Roda Riserva 2006, once again with a comfy earthiness wafting from the glass.

Ctra. Medrano 6

Daroca de Rioja

26373 La Rioja

to reserve: +34 941 44 48 32

www.ventamoncalvillo.com

GPS: N 42° 22' 20" W 2° 34' 50"

The first 3 wines were given to him to taste in unmarked bottles from "a" winery. The most interesting of the wines we tasted that day were from Finca Antigua, their wine called Clavis, 2004 from their vineyard Pico Garbanzo in La Mancha: deep purple with ruby rim, ripe red berries, herbaceous, sweet oak, clarified with egg whites. There were hints of green pepper. Carlos said he detected an aroma of burlap, which I guess is much like the smell of hay. There was no indication on this bottle what the varietals might be, but their Crianza 2007 listed Tempranillo, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah so I’m guessing it was some variety of these. Another highlight was a wine from Bodegas Ramòn Bilbao and their Edición Limitada 2009. This wine is 100% Tempranillo. The wine was a deep red. The first aroma to arise was a smoky, charred toastiness followed by ripe red berries, and prune. This wine had bright acidity and the aromas and flavors presented themselves in complete harmony. I have one more favorite: LZ from Compañia de Vinos de Telmo Rodriguez. This wine set itself apart by adopting a modern, intriguing label, but more importantly it offers good value for money. This is a young (joven) wine and sells in Spain for about 6 euros. It is made of a blend of Tempranillo, Garnacha and Graciano—the 3 classic varietals of La Rioja. I loved the earthiness of this wine and it is truly reminiscent of French wines. (I know that people say that La Rioja is the Bordeaux of Spain, but the earthiness of some of the wines that I tasted bring me back to some Burgundy Pinot’s): damp earth, mushroomy. I know this was not the most expensive wine that I tasted that day, but it was my favorite. Other wines that I had the pleasure of tasting were Distercio, by Florentino Martinez aged in Riojan Oak, a Roda Riserva 2006, once again with a comfy earthiness wafting from the glass.

The first 3 wines were given to him to taste in unmarked bottles from "a" winery. The most interesting of the wines we tasted that day were from Finca Antigua, their wine called Clavis, 2004 from their vineyard Pico Garbanzo in La Mancha: deep purple with ruby rim, ripe red berries, herbaceous, sweet oak, clarified with egg whites. There were hints of green pepper. Carlos said he detected an aroma of burlap, which I guess is much like the smell of hay. There was no indication on this bottle what the varietals might be, but their Crianza 2007 listed Tempranillo, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah so I’m guessing it was some variety of these. Another highlight was a wine from Bodegas Ramòn Bilbao and their Edición Limitada 2009. This wine is 100% Tempranillo. The wine was a deep red. The first aroma to arise was a smoky, charred toastiness followed by ripe red berries, and prune. This wine had bright acidity and the aromas and flavors presented themselves in complete harmony. I have one more favorite: LZ from Compañia de Vinos de Telmo Rodriguez. This wine set itself apart by adopting a modern, intriguing label, but more importantly it offers good value for money. This is a young (joven) wine and sells in Spain for about 6 euros. It is made of a blend of Tempranillo, Garnacha and Graciano—the 3 classic varietals of La Rioja. I loved the earthiness of this wine and it is truly reminiscent of French wines. (I know that people say that La Rioja is the Bordeaux of Spain, but the earthiness of some of the wines that I tasted bring me back to some Burgundy Pinot’s): damp earth, mushroomy. I know this was not the most expensive wine that I tasted that day, but it was my favorite. Other wines that I had the pleasure of tasting were Distercio, by Florentino Martinez aged in Riojan Oak, a Roda Riserva 2006, once again with a comfy earthiness wafting from the glass.